Walking tour of Elizabethan and Jacobean London

30th June 22

Simon Pearson, Head of English, led a group of English Literature Year 12 students on a walking tour of Elizabethan and Jacobean London.

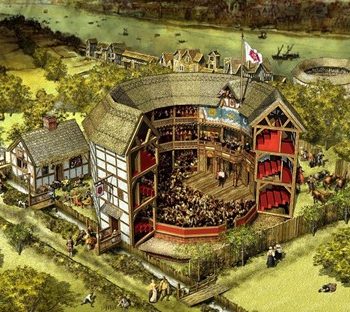

The first stop on our journey was at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. Built in 1599, the original Globe was meant to rival the other great amphitheatre in the Bankside neighbourhood, the Rose which predated it by some twenty-five years. This is the playhouse most associated with Shakespeare – where some of his greatest plays such as Hamlet were first performed. Today’s Globe theatre overlooking the Thames is an authentic replica of the original, but it is not on the actual site. This is located further east, just past Southwark Bridge.

As we made our way towards the site, we passed the Rose Theatre in Park Street. When the foundations of this playhouse were discovered in the 1980s, it made international news. This archaeological site is quite literally the birthplace of English theatre. After a well-publicised campaign, involving famous actors, the site was saved from the developers. You can go and visit the Rose on Saturday mornings.

What struck us most is just how close the Globe and the Rose were to each other. Perhaps only 20 meters or so apart. The rivalry must have been intense. The leading actor at the Rose was Edward Alleyn. He made his name performing great tragic roles in the plays of Elizabethan England’s second greatest dramatist – Christopher Marlowe. Alleyn was not just a great actor but also a very shrewd businessman. He made vast amounts of money opening theatres, taverns, bear-baiting arenas and in property. Like Shakespeare, Alleyn would have lived in Bankside – home to the great amphitheatres and bear-baiting arenas and a vast number of brothels and taverns. Outside the jurisdiction of the City of London, the area had an unsavoury reputation. It was here that Londoners could let their hair down and misbehave – a case of what happens in Southwark stays in Southwark!

When Shakespeare and Alleyn lived here they would have attended St Saviour’s, the local parish church. It is known now as Southwark Cathedral and was the next stop on the tour. Nestling between London Bridge and Borough market, this architectural jewel is well worth a visit. There is a chapel named after John Harvard, the founder of the American university. He was a Southwark resident, before setting off to America to make his fortune and found the most prestigious university in the world.

Shakespeare’s younger brother, Edmund Shakespeare, is buried in the churchyard. A poor actor, Edmund died at a tragically young age – just 27 years-old. His lavish funeral was paid for by his more famous elder brother. We hunted for the memorial stone commemorating Edmund’s short life but were unable to find it. But we did manage to make the acquaintance of Southwark Cathedral’s most famous resident – a black-and-white cat called Hodge whose job is to catch mice. Although there was no evidence of any mousing going on, we can report that Hodge is a very friendly cat who likes his tummy tickled.

Then it was across the Thames via the Millennium Bridge towards St Paul’s Cathedral. Wren’s great baroque masterpiece, which has the second largest dome in the world after St Peter’s in Rome, stands on exactly same site as Old St Pauls, the medieval cathedral which dominated Shakespeare’s London. We climbed the 550 steps leading to the viewing balcony below the steeple, affording us a breath-taking view of the London skyline. The crypt in St Pauls was a real revelation – Nelson’s and Wellington’s monumental tombs are really something to behold.

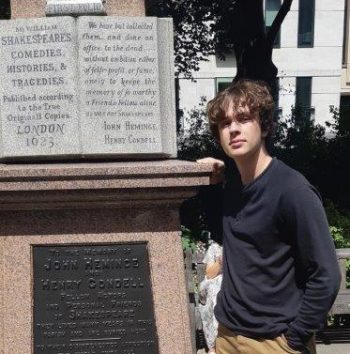

Next up was Aldermanbury, north-east of St Pauls. We were off to see where Shakespeare’s actor-friends, John Heminge and Henry Condell, compiled the First Folio – the collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays. Published six years after Shakespeare’s death, this is the most important book in the English language. There is a monument to Heminge and Condell in the garden square built into the ruins of St Mary’s Church, Aldermanbury. The church was destroyed twice – first in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and then during the Blitz in the Second World War. What was left of the church was transported to America and rebuilt there.

After a quick hydration break, we headed north towards the Barbican. Originally a Roman fortification built into the original London Wall, the Barbican is now an upmarket housing estate and arts complex. It is also home to one of my favourite churches in London – St Giles, Cripplegate. Inside, we marvelled at the beautiful stain-glass window dedicated to Edward Alleyn and found the plaque honouring John Milton – one of the greatest poets in the English language. Milton, along with his father, was interred in St Giles.

Then it was off to the west of the Barbican. The destination was the site of Edward Alleyn’s Fortune Theatre. Alleyn and Henslowe built this revolutionary hexagonal-shaped playhouse because they wanted to rival the newly opened Globe (the Rose closed in 1605 and was quickly demolished). There is not much to see at this site truth to tell – just a plaque on a wall, marking the spot where the Fortune once stood. But this little pocket of London backstreets has a great community vibe and an interesting assortment of pubs and restaurants.

We had now reached the second to last stage of the tour. The spirit may have been willing, but the flesh was lagging. We had covered some 12 km. So, we decided to call it a day at St John’s Square, Clerkenwell. In Shakespeare’s day this was home to the Priory of St John of Jerusalem. In the medieval period, this plot of land was granted to the Knights of St John who had originally travelled to the Holy Land as hospitallers. The original priory building was bombed during the war, but the imposing gatehouse still stands.

In Shakespeare’s day the priory was home to the Master of the Revels. Appointed by the Crown, his job was to vet any new play that had been written, looking out for signs of sedition, profanity, and the like. If the Master of the Revels did not grant you a license, then, there would be no performance of your play, no matter how good the writing. The priory has a beautiful, cloistered herb-garden right next to where the Revel’s Office would have been. And this was where our long journey ended – in a secluded and aromatic herb-garden in the heart of London.

Click here to view the itinerary of the walking tour.

Simon Pearson, Head of Humanities Faculty / English Teacher